In a session on sex-related factors in sports medicine at the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine Annual Meeting, Mary K. Mulcahey, MD, of Tulane University School of Medicine, addressed anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears in female athletes, covering topics such as risk factors for injuries, return to play, and prevention.

“We’re well aware that upward of two-thirds of ACL injuries are the result of noncontact injuries that occur during sudden deceleration and change in direction, largely during landing and cutting and pivoting sports such as soccer, volleyball, and basketball,” Dr. Mulcahey explained. “These have a substantial impact on patients: Surgery and rehabilitation costs in these athletes can be upward of $646 million annually in the United States.” For female athletes, the risk is at least two to four times higher than for their male counterparts, but it can be as much as eight times higher.

Risk factors

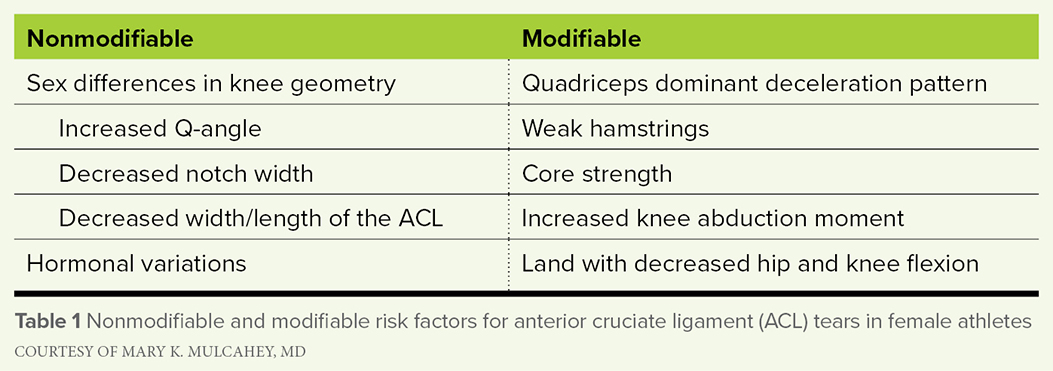

Differentiating between nonmodifiable and modifiable risk factors (Table 1), Dr. Mulcahey identified knee geometry as a prominent nonmodifiable factor. Female athletes have an increased Q-angle and decreased notch width, as well as decreased width and length of the ACL. She also noted that increased posterior slope (> 12 degrees) is a risk factor for all athletes. “That actually is not a sex-related difference,” she said. “I bring it up because it is a really important risk factor for both our male and female athletes.”

Hormonal variations “absolutely play a role,” according to Dr. Mulcahey. “Estrogen and progesterone levels rise and fall throughout the menstrual cycle, and we know that sex hormone receptors are present on several tissues, including skeletal muscle, connective tissue, and bone. Estrogen alters the collagen metabolism and structure. Some studies demonstrate that women in the pre-ovulatory phase are at increased risk for ACL injuries.” Still, she said, “It really is unclear to us how fluctuations in sex hormones can alter the structure and function of the ACL.”

Because “understanding that hormonal influence is crucial,” Dr. Mulcahey said, the question of whether oral contraceptives might mitigate the risk of ACL tear merits exploration. A recent systematic review identified seven studies that examined oral contraceptive use and soft-tissue injury risk. “Unfortunately, only two of those had high-quality evidence, but they demonstrated that oral contraceptive use can decrease the risk of ACL injury and decrease ACL laxity. Hopefully, these medications may serve a therapeutic role in decreasing this sex disparity in ACL injury.”

Turning to modifiable risk factors, Dr. Mulcahey noted that neuromuscular control is important. “Female athletes have a quad-dominant deceleration pattern and weak hamstrings, so those two things together really put the female athlete at high risk,” she said. “When the quads are activated, that pulls the tibia anteriorly and puts a tremendous amount of stress across the ACL.”

Additionally, she said, female athletes tend to have lower core strength than male athletes. “There are absolutely sex-related differences in landing patterns. Women tend to land with increased valgus alignment (i.e., knock-kneed).”

Female athletes also have decreased hip and knee flexion, “So they tend to land with very stiff legs, instead of landing softly and absorbing that force,” she said. “Those two things together are significant risk factors. This is also thought to be related, at least in part, to core strength and proprioception.”

A recent study involving knee kinematics examined sex-related differences in ACL loading, ground reaction forces, and three-dimensional knee kinematics, as well as muscle forces during two movements: 45 degree cut and one-legged hop movements. The investigators extracted ACL forces and strains and found that during hop movements, females had significantly greater peak ACL force and greater strain. Male athletes demonstrated a larger soleus gastrocnemius ratio. “This is something that we don’t hear about often, but it’s sort of analogous to the hamstrings and quads,” Dr. Mulcahey said. “The soleus helps pull the tibia posteriorly, and the gastrocnemius is an antagonist to the ACL.”

Another recent study looked at differences in knee kinetics between male and female athletes that can lead to greater ACL strain when similar loads are applied during a simulated drop vertical jump. The study found that knee abduction moment demonstrated significant differences in female athletes; when normalized for height and weight, the difference was even more significant. “This is one of the most critical risk factors for ACL tears,” Dr. Mulcahey said. “[The study] concluded that increased external loads led to increased medial knee translation force, external knee moment, and knee abduction moment in both male and female athletes, but importantly, females exhibited greater forces and moments at the knee, especially with regard to knee abduction moments.”

Prevention

In terms of injury prevention, considerable research is available, and prevention strategies arising from the findings are “important and very effective,” Dr. Mulcahey said. The programs focus on biomechanical and neuromuscular risk factors, including increased knee abduction angles and limited knee flexion—landing with stiff legs, asymmetrical landing (e.g., landing on one foot), and abnormal ground reaction forces.

A recent study sought “to evaluate the common effective components that are included in these programs and to hopefully develop a tool to assess the quality of ACL neuromuscular performance programs,” Dr. Mulcahey explained. The systematic review identified 18 studies with a total of about 27,000 individuals, 347 of whom had ACL injuries. The study found that neuromuscular training could reduce the risk of ACL injury from one in 54 to one in 111.

“They also found that interventions [geared] toward the younger athletes were much more effective,” she said. “These programs should absolutely be implemented at the middle school level, which is more effective than waiting until college and certainly the professional level.”

Focusing on landing stabilization and lower body strength exercises “helps improve the prophylactic effect,” Dr. Mulcahey said. “Using trained implementers, with some sort of instructional workshop and educational component to make sure everybody understands how to do the exercises, is important; incorporating lower body strengthening and landing mechanics are also important take-away points.”

Back in the game

Addressing return to play, Dr. Mulcahey said patients recovering from ACL reconstruction “absolutely should meet specific criteria with regard to range of motion, strength, neuromuscular control, proprioception, and completing subjective knee scores. These tests should be done under an endurance situation, too, because that’s when the athlete is fatigued [and] at higher risk for injury.”

Components that may be incorporated into a functional sports assessment include hop testing, single-leg squat, lateral agility-type drills, drop to jump, and deceleration drills.

Dr. Mulcahey also addressed the psychological factors involved in return to play. “These are applicable to both our male and female athletes,” she said. “By understanding and identifying these factors, we can better understand our athletes’ psychological readiness to return to play.”

For example, a study demonstrated that younger patients with lower psychological readiness to return to play are at high risk of sustaining a second ACL tear. “Psychological counseling may need to be incorporated in parallel to physical recovery to help increase the chances of having our athletes return to sport safely,” Dr. Mulcahey said.

Fear of re-injury “is the primary emotional factor affecting return to play,” Dr. Mulcahey said. “It is closely associated with kinesiophobia, which is a heightened fear of movement, and subsequent re-injury and is also associated with lower self-reported knee function and lower rates of return to play.”

Expectations and assumptions about recovery should be addressed, Dr. Mulcahey said. “Athletes’ initial expectations about their surgery may be skewed, and oftentimes they’re not fully prepared for postoperative rehab. When they have unrealistic expectations, that can lead to decreased confidence and decreased self-efficacy. It’s important for us to spend some time talking to them about what to expect.”

Terry Stanton is the senior science writer for AAOS Now. He can be reached at tstanton@aaos.org.