At the AAOS 2019 Annual Meeting Instructional Course Lecture titled “Top Tips for Your Practice,” AAOS President Kristy L. Weber, MD, offered pointers for assessing lesions and masses—“lumps and bumps and more”—that orthopaedic surgeons may see in their patients.

Dr. Weber, professor and chief of orthopaedic oncology at the University of Pennsylvania, offered her “top eight tips” for evaluating soft-tissue masses:

- Know that benign lesions are “way more common” than malignant ones—by “about 100 to one,” she said.

- Follow an algorithm consisting of history, examination, imaging, and biopsy, if needed. “It is critical even in a busy practice to ask the right questions and follow these steps,” she said.

- Know that most masses need imaging.

- Consider MRI with contrast “if you are looking at something where you are not quite sure,” she said.

- Order ultrasound imaging or MRI with contrast to confirm “cystic” masses.

- Biopsy anything indeterminate.

- Always send tissue for histopathologic examination, even if it is classified radiographically or clinically as a cyst or infection.

- Refer any case to an orthopaedic oncologist if you are unsure about it.

Dr. Weber noted that among cancers, those affecting the soft tissues are relatively rare, and those of bone and joints are even more rare. Of the 1.8 million new cases of cancer and 607,000 cancer-related deaths estimated for 2019 by the American Cancer Society, about 13,000 cases (5,300 deaths) will originate in soft tissue and 3,500 (1,000 deaths) in bone and joints.

Soft-tissue challenges

Summarizing the issues that can surround and confound the detection of soft-tissue sarcoma, Dr. Weber said, “We often arrive late to the problem. The fate may be predetermined because size matters. People sometimes do the wrong operation based on the wrong diagnosis. They think, ‘This is a lump, it must be a lipoma,’ and they shell it out like a pea, but it occasionally turns out to be a sarcoma.”

In assessing a soft-tissue mass, the surgeon should follow an algorithm when taking the history that asks how long the mass has been growing, whether it is enlarging (and how quickly), and whether it is painful. “Soft-tissue sarcomas often don’t cause pain, and this can be the problem, as patients and some doctors assume that painless masses are benign,” Dr. Weber said, adding that an abscess is more likely to be painful.

The history should also cover past trauma and occurrence of cancer. For the latter query, Dr. Weber advised, “Ask twice,” noting that some patients may neglect to mention an incidence of cancer treated years ago.

During physical examination, concerning signs include size greater than 5 cm, location deep to the fascia, and proximal location in the extremities. “Anything that’s big and deep and firm, often in the upper thigh,” is cause for elevated suspicion, she said. With the arm and leg, Dr. Weber advised, “Actually examine the extremity. Check the regional lymph nodes. Some subtypes of soft-tissue sarcoma can metastasize into the lymph node chain.”

In evaluating hands and feet with nodules, “Ask yourself, ‘Is this typical for a ganglion cyst?’” she said. If not or if one is not sure, consider an ultrasound to confirm a cystic (versus solid) lesion, or direct the patient to a specialist to rule out malignancy—specifically epithelioid or clear cell sarcoma. “These are nasty sarcomas,” Dr. Weber said. “They are insidious; they spread through the lymph node chain, and they kill people.”

The right image

Imaging should be performed for most soft-tissue tumors. Plain radiographs are rarely definitive but may yield useful information, including:

- scattered calcifications (seen in 30 percent of synovial sarcomas)

- peripheral mineralization, suggesting myositis ossificans

- phleboliths or periosteal erosions indicating possible vascular malformation

Ultrasound is an inexpensive alternative in an era of cost consciousness, she said. “You can use it to look for fluid and be sure you are dealing with a ganglion or a Baker cyst and can also assess for local recurrence after resection of superficial sarcomas. It’s cheap, quick, and ideal for assessing hand and foot lesions,” she said.

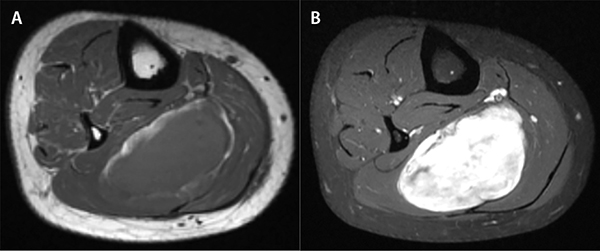

MRI, Dr. Weber said, “is the workhorse for soft-tissue tumors in orthopaedic oncology.” This modality, with contrast, is used to distinguish determinate versus indeterminate masses. “If the nature of the lesion can be definitively determined on MRI—a lipoma, ganglion cyst, vascular malformation, muscle injury—you do not need a biopsy. If you can’t say for sure what it is, you [have] to biopsy it,” she advised (Fig. 1). This guidance especially applies to a large lesion in an extremity. Samples should be obtained for histopathologic assessment, either by needle biopsy or an open procedure. An orthopaedic oncologist should often be consulted prior to an open biopsy in case a referral is preferable.

Dr. Weber said she commonly sees patients who have been told by a physician that they have a lipoma, but the diagnosis needs to be confirmed in instances when “they didn’t have an image or the image was read inaccurately.” In the extremities, an MRI scan of a simple or atypical lipoma shows signal intensity on all sequences as identical to surrounding fat. “These benign lesions do not generally require a biopsy,” she said.

An apparent lipomatous lesion in the retroperitoneum “is a different story,” Dr. Weber said. “A retroperitoneal fat lesion might be a well-differentiated liposarcoma.”

A suspected Baker cyst on an MRI scan without contrast may actually be a myxoid liposarcoma, as contrast is necessary to differentiate between cystic and solid lesions.

Dr. Weber said that an excisional biopsy, in which a lesion is “shelled out like a pea,” is acceptable “only if you are 100 percent sure that it is a benign lesion prior to surgery.” Excisional biopsy should not be performed on indeterminate lesions, which require preoperative biopsy.

In terms of biopsy method, Dr. Weber said open biopsy has the advantages of providing adequate tissue sampling for diagnosis and tissue for other studies or research protocols. Disadvantages include problems with incision placement and biopsy technique.

Image-guided needle biopsy has gained favor as an accurate and clinically useful technique that is efficient and cost-effective.

Specialty specifics

Dr. Weber concluded with a rundown of “mistakes to avoid, by specialty.” In the general orthopaedic setting, such errors could include excising a lipoma or cyst without imaging, or débriding an abscess without appropriate clinical or imaging confirmation.

Under adult reconstruction, Dr. Weber showed the case of a woman with a popliteal mass that was noted 1.5 years previously to be classified as a Baker cyst based on MRI without contrast. After it continued to grow, MRI with and without contrast and then needle biopsy revealed it to be myxoid liposarcoma. “Noncontrast MRI will not differentiate solid and cystic lesions with 100 percent accuracy,” Dr. Weber said.

In sports medicine, most pain symptoms are the result of injury. However, if symptoms persist despite conservative management, further workup and imaging should be performed.

In trauma cases, Dr. Weber advised, longstanding draining wounds may camouflage squamous cell carcinoma. “When there is a change in appearance with more hypertrophic tissue, you have to start worrying about transformation,” she said. “You need to biopsy the lesion.”

In pediatrics, an initial traumatic injury may lead to a mindset that an associated, persistent mass is related to the initial trauma, but it may be revealed by MRI and biopsy to be a coinciding malignant process.

Terry Stanton is the senior science writer for AAOS Now. He can be reached at tstanton@aaos.org.