Achilles tendon rupture is a common sports injury that orthopaedic surgeons treat. It also remains one of the most controversial injuries with respect to operative versus nonoperative options. Certain questions, from both specialists and generalists, inevitably surface in the management of Achilles tendon rupture, including: How should we counsel patients about their treatment options? Should we recommend surgery or advise against it? How should the patient’s occupation, health, and activity level influence the decision process?

Studies comparing operative and nonoperative management are frequently published, often with conflicting results. Other debates focus on the need for imaging studies and optimal postoperative management. In an effort to provide best practice advice, AAOS published a clinical practice guideline (CPG) on the diagnosis and treatment of acute Achilles tendon rupture in 2009. This article addresses how to use the CPG in clinical practice as the foundation for a shared decision-making (SDM) process. Here, SDM has been defined as “an approach where clinicians and patients share the best available evidence when making decisions, and where patients are supported to consider options, to achieve informed preferences.”

Using the CPG to guide discussions and decisions

As detailed in the AAOS CPG, Achilles tendon ruptures can be treated with or without surgery (limited strength recommendation). In a situation of clinical equipoise, where either treatment is likely to yield a similar result, sharing the best evidence with the patient is important for sound decision-making. Unlike an open, displaced tibia fracture—where the need for surgical débridement and fixation is clearly in the patient’s best interest nearly all of the time—the treatment of an Achilles tendon rupture has variable risks and benefits depending on the patient and his or her preferences.

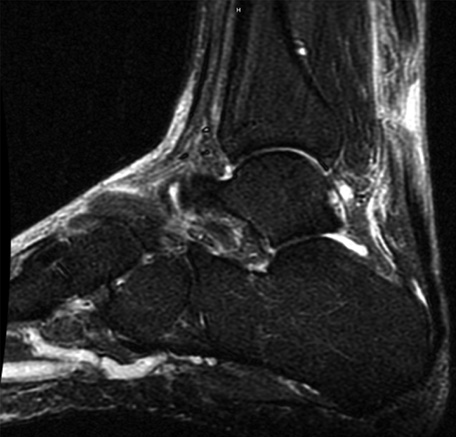

The CPG can be used as a foundation for both the diagnostic portion of the visit and the SDM process. It is important to perform a thorough physical examination, including the Thompson test, to diagnose a rupture (consensus recommendation). Patients who request an MRI with a positive Thompson test can be reassured that an MRI is not required based on the CPG. Conversely, if findings are equivocal, MRI can be a helpful adjuvant to diagnosis.

As part of the history-taking, discuss medical comorbidities that may impact the patient’s outcome. In patients with comorbidities—such as diabetes, neuropathy, immunocompromised states, tobacco use, peripheral vascular disease, obesity, and sedentary lifestyles—patients should be informed that a consensus of orthopaedic surgeons has agreed that surgery is not recommended. In this setting, the increased risk of complications may exceed the potential benefit of surgery. However, this recommendation is not absolute. An individual patient’s characteristics should be considered.

In a patient without significant medical comorbidities, both nonoperative and operative management are considered. After establishing both of these options, use the guidelines to discuss treatment. For example, counsel patients that regardless of treatment, an immobilization device—often, a boot with heel lifts (moderate strength recommendation)—is employed. Advise patients that they will initiate early weightbearing and provide them with a detailed, week-by-week physiotherapy plan based on a published protocol (moderate strength recommendation).

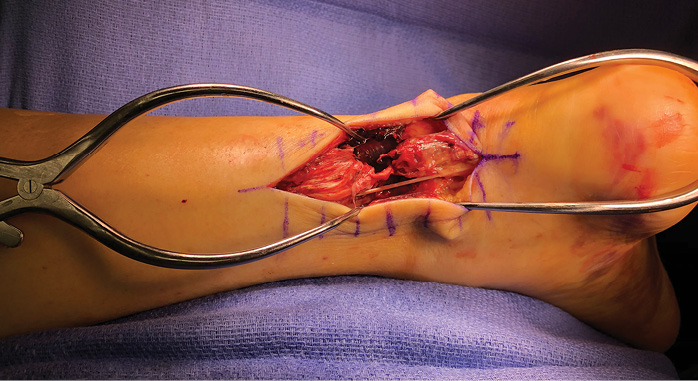

After discussing similarities between the treatment pathways, present the pros and cons of each option. Explain that the main difference between the two treatments is that surgery entails surgical risks. Regarding the risks of nonoperative treatment, explain that the evidence is contradictory about a higher risk of rerupture and lower strength, with a recent study suggesting this risk is higher in young men. Patients should be advised that there are multiple approaches to surgical repair, with a lower risk of wound complications with a percutaneous technique. Conclude the conversation by letting the patient know that the decision is his or her own.

An area for improvement

A challenge with the AAOS CPG is the absence of evidence for or against the use of antithrombotic treatment in patients with an Achilles tendon rupture. There has not been a definitive study since the guidelines were published, though a retrospective healthcare management database review showed a low overall incidence of symptomatic deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE). Therefore, based on the limited available evidence, in practice, we generally limit chemoprophylaxis to a daily baby aspirin, unless a patient has a personal history of DVT/PE, genetic factors, family history, and/or his or her primary care physician recommends prophylaxis.

Conclusion

Despite numerous studies comparing nonoperative and operative options, the optimal treatment for an acute Achilles rupture remains controversial. Although the CPG helps tremendously with counseling patients regarding diagnosis, imaging, and the role of functional rehabilitation, the most important question of whether to undergo surgery must be decided on a case-by-case basis. The CPG is an important tool to help patients make informed decisions regarding their treatment, and it helps practitioners preserve the ethical practice of maintaining patient autotomy.

Casey Jo Humbyrd, MD, is chief of the foot and ankle division at Johns Hopkins.

Nigel Hsu, MD, is a foot and ankle orthopaedic surgeon at Johns Hopkins.

Reference

- Elwyn G, Coulter A, Laitner S, et al: Implementing shared decision making in the NHS. BMJ 2010;341:c5146.

- Willits K, Amendola A, Bryant D, et al: Operative versus nonoperative treatment of acute Achilles tendon ruptures: a multicenter randomized trial using accelerated functional rehabilitation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010;92:2767-75.

- Reito A, Logren HL, Ahonen K, et al: Risk factors for failed nonoperative treatment and rerupture in acute Achilles tendon rupture. Foot Ankle Int 2018;39:694-703.

- Patel A, Ogawa B, Charlton T, et al: Incidence of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism after Achilles tendon rupture. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012;470:270-4.