The deltoid is the largest muscle in the shoulder and provides most of the power in shoulder motion. However, it also can produce a muscular imbalance leading to asymmetric wear. An example of this is in patients with rotator cuff arthropathy where the concavity-compression of the humeral head on the glenoid is lost and the deltoid is unopposed, translating the humerus superior and causing asymmetric wear, poor function, and pain. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA) addresses the deltoid’s unopposed force by flipping the articulation with a spherical glenoid and a semi-constrained humeral socket, which converts the action of the deltoid from a destabilizing superiorly directed shear force into a stabilizing rotational force that elevates the arm and stabilizes the articulation.

From 1985 to 1991, Paul Grammont, MD, designed the Delta III, a semi-constrained RTSA that placed the center of rotation (COR) medially to tension the deltoid with a valgus 155-degree neck-shaft angle (NSA) and a medialized hemispheric glenoid. Dr. Grammont emphasized that this implant was a non-anatomic arthroplasty designed to resist the shear of the deltoid, and, theoretically, lengthening the deltoid would increase its mechanical advantage. However, the alteration of the deltoid and the position of the glenohumeral COR resulted in clinical problems, including a high rate of prosthetic abutment (notching), which causes wear debris, a de-tensioning of the rotator cuff, and an alteration of the deltoid contour and function. Many other reverse shoulder designs have embraced non-anatomical reconstruction with humeral distalization, resulting in similar clinical problems. To address these issues and still produce an RTSA that resists the shear of the deltoid, reconstruction with glenoid-sided lateralization and an inset 135-degree NSA on the humeral side was introduced to produce a more anatomic reconstruction of the premorbid glenohumeral joint.

Lateralization of the COR was achieved with a glenosphere that was two-thirds of a sphere rather than a hemisphere. To accommodate the lateralized glenosphere and maintain a glenohumeral relationship with closer-to-normal alignment, an anatomic inclination of the humerus was introduced with an NSA of 135 degrees that insets into the humeral metaphysis. The rationale behind this change to a more anatomically aligned RTSA was to diminish scapular notching by moving the COR away from the glenoid. Restoring the natural deltoid contour, maximizing the impingement-free arc of motion, and optimizing the muscle-tendon length of the rotator cuff resulted in increased rotational strength and function.

Recent results of clinical studies of this more anatomically aligned RTSA have demonstrated the reduction of prosthetic impingement (notching) and improved rotational strength with durable outcomes at 10 years. This improvement may be due to the restoration of the humeral scapular relationship closer to the anatomical state, resulting in a closer approximation of the pre-morbid tensioning of the remaining rotator cuff muscles. With medialization, rotator cuff muscles slacken and the deltoid loses compressive forces. On the other hand, a lateralized COR restores stability by increasing deltoid compression on the humerus. If components are placed too far medially, the deltoid insertion on the humerus becomes medial to the origin of the deltoid on the scapula, which places a distractive force on the prosthesis and results in instability. Additionally, when the arm is lengthened, the rotator cuff’s force vector becomes more oblique, producing less rotational strength.

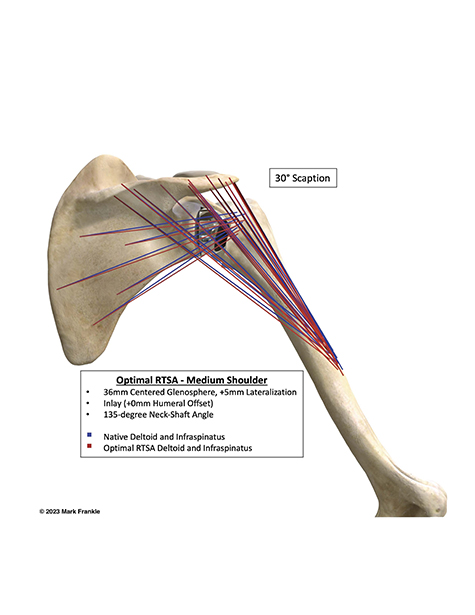

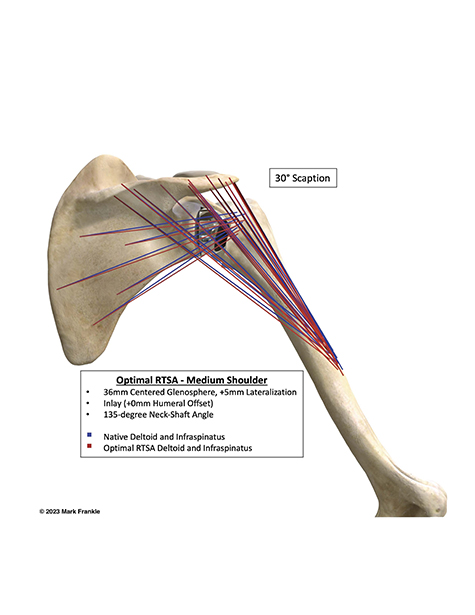

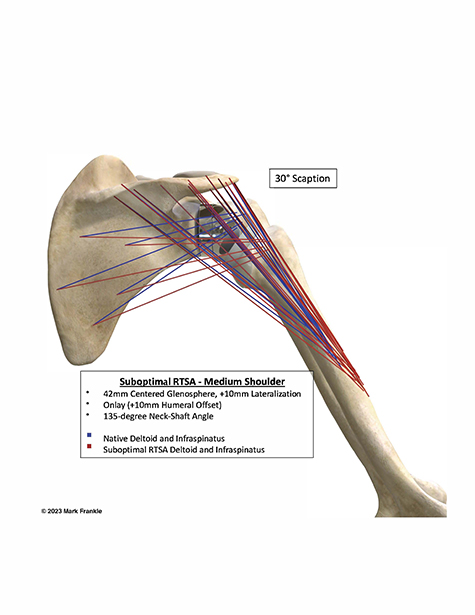

Additionally, biomechanical and 3D computer modeling has demonstrated that a more anatomically aligned restoration with a lateralized glenosphere, an inlay humerus with the socket placed at the anatomic neck plane, and an anatomic NSA best restores native deltoid and rotator cuff muscle-tendon lengths (Fig. 1). Non-anatomic reconstruction with humeral distalization leads to suboptimal muscle-tendon lengths (Fig. 2). Lateral glenosphere COR and 135-degree NSA showed the greatest range of impingement-free motion. Even though optimal muscle lengthening is not known at this point, restoring the native relationship of the shoulder will theoretically provide the benefits of deltoid wrapping and anatomic tensioning of the rotator cuff to improve joint stability, active range of motion, and muscle function.

Christian M. Schmidt II, MD, is an orthopaedic surgery resident in the Department of Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine at the University of South Florida Morsani College of Medicine in Tampa, Florida.

Mark A. Frankle, MD, FAAOS, is an orthopaedic surgeon in the Department of Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine, University of South Florida Morsani College of Medicine in Tampa, Florida, and director of the shoulder service at the Florida Orthopaedic Institute in Tampa.