Orthopaedic surgeons are essential partners in the care of polytrauma patients, but fractures alone rarely kill. The goal is not only to fix bones and restore function but also to stabilize physiology, protect the brain, and prevent death — key priorities in the first few hours after a patient’s arrival. Understanding the tempo of trauma management is critical to making the right decisions at the right time.

This article summarizes key evolutions in trauma care over the past decade, emphasizing the data for early hemorrhage control, the need for rapid resuscitation, and the consequences of delayed intervention, particularly for patients with concomitant brain injury and hemorrhagic shock. Although traumatic brain injury (TBI) is the most common cause of trauma-related death, hemorrhage remains the most preventable.

The clock is ticking on hemorrhage control

The urgency of controlling bleeding is well established. A 2023 systematic review by Lamb et al., covering 24 studies and more than 10,000 trauma patients, found that nearly 70% of studies showed a significant link between delayed hemostatic intervention and increased mortality. Although definitions of “delay” varied, the overarching message was clear: Mortality increases with each minute lost, a finding further confirmed in additional literature. Tien et al. reported that at a Canadian level I trauma center, 40% of patients who died from hemorrhage had pelvic bleeding with delayed access to definitive care.

Although it is outside the scope of this article to review in depth, hemorrhage from complex fracture is an exceptionally difficult problem for trauma surgeons, with significant implications for long-term reconstructive options. The decisions that trauma surgeons make in the moment to control exsanguinating hemorrhage from the pelvis are made with the knowledge that each moment of delay increases the risk of death.

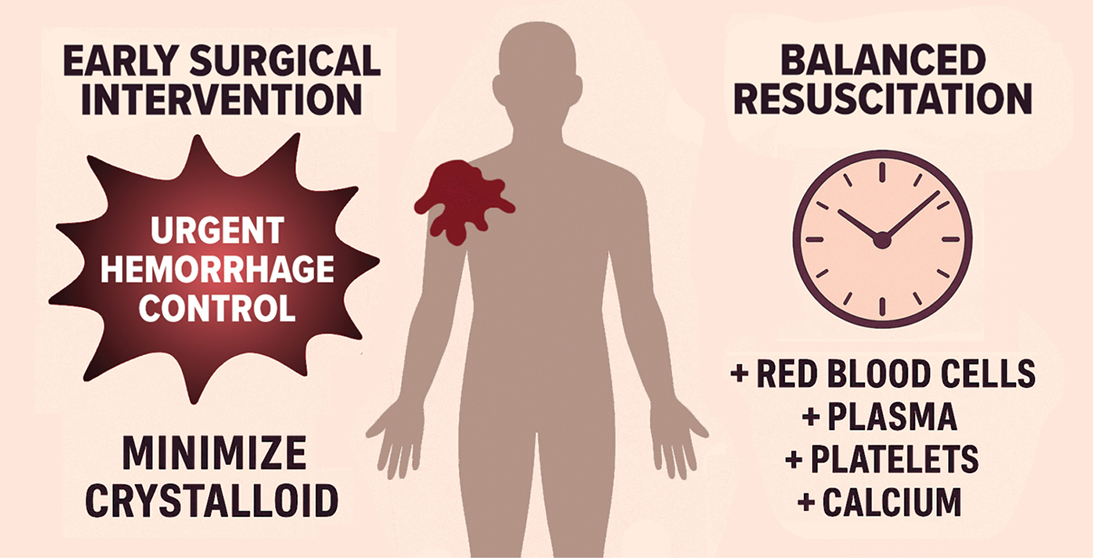

Resuscitation strategy: Timing and balance matter

Alongside mechanical control of bleeding, early balanced resuscitation is essential. The PROPPR trial offered high-level evidence that a 1:1:1 transfusion strategy of plasma, platelets, and red blood cells led to faster hemostasis and a significant reduction in early deaths from exsanguination, even if overall mortality differences were not statistically significant. The time to initiate this balanced resuscitation is as important as the time to hemorrhage-control maneuvers; a subanalysis of PROPPR showed that each one-minute delay in massive transfusion activation was associated with a 5% increase in mortality, regardless of transfusion ratios. Deeb et al. reported that each one-minute delay in initiating blood products increased the odds of 30-day mortality by 2%. These data highlight and expand upon the hemorrhage-control data presented above to drive the thinking of trauma surgeons during initial resuscitation. Decisions that, in retrospect, may seem overly invasive or aggressive must be considered in the frame that they are made; there is simply no time for partial measures in trauma, and a single extra minute to decide will measurably increase mortality risk.

Adjuncts to balanced resuscitation, such as tranexamic acid, offer clear time-dependent benefits. Tranexamic acid is most effective within two hours of injury, with reduced efficacy thereafter, particularly in patients with both hemorrhage and TBI. The CRYOSTAT-2 trial confirmed the feasibility of high-dose cryoprecipitate within 90 minutes of arrival, although it did not meet its 28-day mortality endpoint. This study should be viewed with caution, as delayed hemorrhage control was identified as a confounding variable in the trial’s neutral outcome. More rapid hemorrhage control may have resulted in a more robust impact of early cryoprecipitate use.

Physiological understanding of trauma resuscitation has also evolved and overlays the priority of balanced resuscitation. Ditzel et al. proposed expanding the classic “lethal triad” (acidosis, hypothermia, coagulopathy) into the “lethal diamond” by adding hypocalcemia, a critical mediator of coagulation and myocardial performance. Calcium depletion during massive transfusion is common and increasingly recognized as a modifiable contributor to trauma mortality.

REBOA: A tool with promise and limits

Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) is a minimally invasive adjunct for noncompressible pelvic hemorrhage. By inflating a balloon in the aorta (zone III), it augments central perfusion and buys time for surgical or interventional control. Though relatively new, it expands the traditional tool kit for managing exsanguinating pelvic bleeding.

Although theoretically satisfying, the evidence for REBOA efficacy is mixed. UK-REBOA is the only large, randomized trial on this technique and found no overall survival benefit, as well as potential harm, in trauma patients with exsanguinating hemorrhage. However, subgroup analyses in pelvic trauma were limited. In contrast, an analysis of a prospectively maintained registry reported a significant reduction in mortality with REBOA use, compared to open aortic occlusion, in patients with traumatic arrest. Larger retrospective studies in the United States with broad inclusion criteria raise concern about REBOA use being associated with increasing rates of limb loss, acute kidney injury, and death. Joint statements from large national organizations recommend use only in centers with trained surgeons immediately available, well-established institutional protocols, and immediate access to definitive intervention.

As with any rapidly evolving field, it’s important to note that these guidelines predate both the UK-REBOA and Joseph et al. studies — two large investigations that raise concerns about REBOA’s risks and limited efficacy. Further high-quality, pelvic-specific, randomized trials are needed to better define the role of REBOA, which will likely be difficult to do as the trend appears to be toward more constrained indications for use.

TBI and the hidden consequences of hypotension

Although not typically managed by orthopaedic surgeons, TBI remains a major contributor to trauma mortality. Avoiding secondary injury due to hypotension and hypoxemia is the overriding therapeutic objective during the first several hours and days after a complex injury, and it may be the most important modifiable factor contributing to positive neurologic recovery.

Even brief hypotension worsens neurologic outcomes, and Spaite et al. have shown that lower prehospital systolic blood pressure is independently associated with increased mortality in severe TBI. This finding reinforces the imperative for rapid hemorrhage control in blunt multisystem injury and, again, drives trauma surgeon decision-making related to the urgency of hemorrhage control and resuscitation. Rapidly stopping bleeding can make a significant difference in avoiding intermittent episodes of hypotension associated with transient response to transfusion in the face of ongoing bleeding. This physiological relationship (i.e., the imperative for hemorrhage control and avoidance of hypotension) has direct implications for orthopaedic surgeons, as delays in fracture stabilization are sometimes necessary to prioritize hemorrhage control and physiologic stabilization. Decisions to delay general anesthesia or large orthopaedic reconstructions, with concomitant high blood loss, may also be driven by a desire to avoid induction-associated hypotension or significant intraoperative blood loss.

In patients with TBI and hypotension, the margin for error narrows, as even single episodes of hypotension likely worsen neurologic outcomes, and coordinated trauma care becomes essential. Over the past decade, a waterfall of data has emerged to show that time is not a neutral variable in a patient with severe hemorrhagic shock, and the minutes really do matter. Balanced blood transfusion, early activation of massive transfusion systems, damage-control resuscitation, and rapid hemorrhage-control strategies have meaningfully impacted patient mortality. Cooperation and collaboration across teams and shared understanding of the rapidly changing physiology of a multiply injured patient are essential for a high-performing trauma team. Early, collaborative decision-making will align surgical priorities with the realities of survivability.

Mackenzie Cook, MD, FACS, is an associate professor of trauma, critical care, and acute care surgery at Oregon Health & Science University. He is an associate general surgery program director and has a deep passion for treating critically ill and profoundly injured patients, as well as improving teams and training people to do the same.

References

- Holcomb JB, Tilley BC, Baraniuk S, et al. Transfusion of plasma, platelets, and red blood cells in a 1:1:1 vs a 1:1:2 ratio and mortality in patients with severe trauma: The PROPPR randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313(5):471-82. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.12

- Meyer DE, Vincent LE, Fox EE, et al. Every minute counts: Time to delivery of initial massive transfusion cooler and its impact on mortality. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;83(1):19-24. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000001531

- Lamb T, Tran A, Lampron J, et al. The impact of time to hemostatic intervention and delayed care for patients with traumatic hemorrhage: A systematic review. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2023;95(2):267-75. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000003976

- Douglas M, Obaid O, Castanon L, et al. After 9,000 laparotomies for blunt trauma, resuscitation is becoming more balanced and time to intervention shorter: Evidence in action. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2022;93(3):307-15. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000003574

- Tien HC, Spencer F, Tremblay LN, et al. Preventable deaths from hemorrhage at a level I Canadian trauma center. J Trauma. 2007;62(1):142-6. doi:10.1097/01.ta.0000251558.38388.47

- Costantini TW, Burlew CC, Jenson WR, et al. Pelvic fracture bleeding control: What you need to know. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2025;99(3):319-327. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000004609

- Deeb AP, Guyette FX, Daley BJ, et al. Time to early resuscitative intervention association with mortality in trauma patients at risk for hemorrhage. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2023;94(4):504-12. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000003820

- Crash-3 trialcollaborators. Effects of tranexamic acid on death, disability, vascular occlusive events and other morbidities in patients with acute traumatic brain injury (CRASH-3): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10210):1713-23. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32233-0

- PATCH-Trauma investigators and the ANZICS Clinical Trials Group, Gruen RL, Mitra B, et al. Prehospital tranexamic acid for severe trauma. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(2):127-36. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2215457

- Osawa I, Goto T, Roberts I. Tranexamic acid for trauma: Optimal timing of administration based on the CRASH-2 and CRASH-3 trials. Br J Surg. 2025;112(4):znaf079. doi:10.1093/bjs/znaf079

- Davenport R, Curry N, Fox EE, et al. Early and empirical high-dose cryoprecipitate for hemorrhage after traumatic injury: The CRYOSTAT-2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2023;330(19):1882-91. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.21019

- Ditzel RM Jr., Anderson JL, Eisenhart WJ, et al. A review of transfusion- and trauma-induced hypocalcemia: Is it time to change the lethal triad to the lethal diamond? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020;88(3):434-9. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000002570

- Jansen JO, Hudson J, Kennedy C, et al. The UK resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta in trauma patients with life-threatening torso haemorrhage: the (UK-REBOA) multicentre RCT. Health Technol Assess. 2024;28(54):1-122. doi:10.3310/LTYV4082

- DuBose JJ, Scalea TM, Brenner M, et al. The AAST prospective Aortic Occlusion for Resuscitation in Trauma and Acute Care Surgery (AORTA) registry: Data on contemporary utilization and outcomes of aortic occlusion and resuscitative balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA). J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;81(3):409-19. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000001079

- Joseph B, Zeeshan M, Sakran JV, et al. Nationwide analysis of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta in civilian trauma. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(6):500-8. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0096

- Brenner M, Bulger EM, Perina DG, et al. Joint statement from the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma (ACS COT) and the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) regarding the clinical use of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA). Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2018;3(1):e000154. doi:10.1136/tsaco-2017-000154

- Spaite DW, Hu C, Bobrow BJ, et al. Mortality and prehospital blood pressure in patients with major traumatic brain injury: Implications for the hypotension threshold. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(4):360-368. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2016.4686