The sacrum, as the word implies, is sacred. Both the ancient Greeks and ancient Romans suspected that the sacrum was seat of the soul, e.g., the core of one’s being. This perspective likely derived from the ancient Egyptians who connected the spinal column and its supporting sacrum with Osiris, god of resurrection. Also, because of its location, the sacrum protects the uterus, the generative organ. Moreover, the sacrum, being among the thickest and densest of bones, resists natural degradation more than other osseous structures. Therefore, its exalted status makes sense. Indeed, in both Jewish and Islamic eschatology, on the Day of Judgment, when those properly buried are resurrected, the process will begin with the sacrum and spread from there.

Among Eastern yoga religions, the sacrum is also a sacred bone, the seat of dominant energy, called Kundalini, and forms the second chakra’s location, which controls procreation and creativity.

From fish to humans: tracing the sacrum’s evolutionary journey

Theology aside, the sacrum has an interesting evolutionary history. Fish do not have sacra; instead, the pelvic fins attached via a primitive acetabulum to a small pelvic bone, which floats free against the pelvic ribs, just as a human’s scapulae floats free against its thoracic ribs. As primordial creatures emerged from the sea, greater stability, especially for the hindlimbs, required pelvic stabilization when weight-bearing. The first lobe-finned fish, walking on the sea floor, developed heavy ligaments connecting the primitive pelvis to enlarged ribs of the pelvic vertebrae. When Tiktaalik roseae, a land walking, alligator-shaped fish emerged in the late Devonian, some pelvic ribs had already fused, suggesting a primitive sacrum.

Later, amphibians and reptiles developed first one, and then two, segment sacra, articulating with the pelvis for increased ambulatory stability. More advanced vertebrates have fully formed sacra, consisting of several fused vertebrae, which attach to the pelvis through synovial sacroiliac joints. In birds, the sacrum is fused to the pelvis for additional stability during flight. As if to confirm the human sacrum’s evolutionary history, the bone remains segmented until adult life.

The coccyx also enjoys a fascinating evolutionary history. Most vertebrates have tails, yet humans and closely related anthropomorphic apes do not. Indeed, the absence of tails is exceedingly rare throughout the subphylum Vertebrata. Bony and cartilaginous fish have tails, as do all amphibia, except for frogs and toads, who have them during their tadpole phase of life.

Reptiles have some of the longest tails of all. Who has not marveled at the 80-segment tail on Diplodocus dinosaurs whose skeletal remains dominate science museums around the world? Birds have tails, except for New Zealand’s flightless kiwi.

Among mammals, all carnivores (except the specially bred-Manx cat) have tails, as do the quadrupeds they chase. The giraffe has an eight-foot-long flyswatter attached to its rear end. Among rodents, only the capybara lacks a tail. Almost all primates have tails, some so remarkably prehensile that they function as a fifth terminal grasping appendage. (This author, for one, would certainly have found a prehensile tail useful during surgery, to hold a Bennett retractor while plating a humerus, or to turn the cannula’s waterflow on and off during solo arthroscopic surgery.)

Why humans lost their tails—and the genetic link to spinal disorders

Initially, physical anthropologists assume that loss of a tail improves upright bipedal gait about 6 million years ago. The availability of modern genetic analysis allows researchers to look back in time and understand how and when certain genetic modifications occur in a lineage. In humans’ ancestral line, the tail suppressing event occurred about 25 million years ago. With respect to tails, Xia et al. have demonstrated that inserting an Alu element into an intron of the T-box transcription factor T gene pairs with an ancestral Alu element to lead to a hominid-specific reverse splicing event that suppresses tail formation. To test their hypothesis, the researchers used the CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing tool to insert the Alu element in the mouse genome, which resulted in mice with rudimentary or absent tails. The researchers noted that, in addition to loss of tail, some mice also developed neural tube defects resembling the spina bifida group of disorders that affect 1 in 1,000 human births. Thus, there appears to be a genetic connection between tail growth suppression and failure of neural tube closure.

The sacroiliac joint: anatomy, pathology, and clinical assessment

As the human body’s largest synovial articulation, the sacroiliac (SI) joint possesses hyaline cartilage surfaces and true synovial linings, as well as a strong surrounding capsule constructed from powerful ligaments. Hence, the SI joint can develop diseases that can involve any such structure, including viral, septic or tuberculous pyarthrosis, crystal arthropathies, and auto-immune joint inflammation, including ankylosing spondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis, and many others. Situated along the pathway of many spinal nerves, the SI joints may be subjected to referred pain arising elsewhere.

Physical examination of the sacrum, coccyx, and SI joints is relatively straightforward since the bone is superficial, and the surrounding ligaments permit only very limited motion.

The first step in any assessment of SI joint dysfunction is to ask the patient to point with one finger at the most painful region. Palpation of the SI joints is easy while the patient stands, slightly bent forward, which brings the posterior superior iliac spines into clear view. The pelvis overlaps the upper part of the SI joints, but the rest of the joint is subcutaneous.

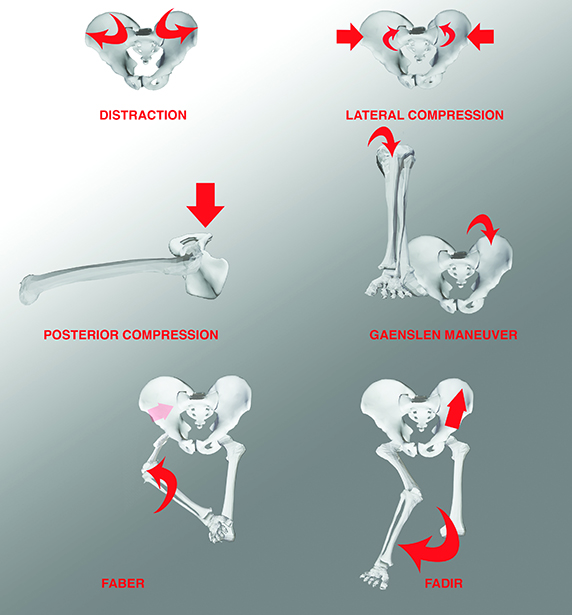

Test the SI joint’s ligaments with standard maneuvers that stress various ligament groups in sequence while applying distraction, compressive, and rotational forces to each hemipelvis, as shown in Figure 1.

The sacrum and its associated structures are more than anatomical curiosities — they are central to human evolution, cultural symbolism, and clinical practice. From its revered status in ancient theology to its role in upright gait and genetic mysteries, this bone tells a story that bridges history, biology, and medicine. Understanding its anatomy and pathology remains essential for orthopaedic surgeons, while its evolutionary and cultural significance reminds everyone that even the most familiar structures carry profound meaning.

Stuart A. Green, MD, FAAOS, is cofounder and past president of the Limb Lengthening and Reconstruction Society, past president of the Association of Bone and Joint Surgeons, and an attending surgeon at the Tibor Rubin Long Beach VA Medical Center in California. He is also a member of the AAOS Now Editorial Board.

References

- Sugar O. How the sacrum got its name. JAMA. 1987;257(15):2061-2063. doi:10.1001/jama.1987.03390150077038

- Bonnan MA. The Bare Bones: An Unconventional Evolutionary History of the Skeleton. Bloomington: Univ Indiana Press; 2024.

- Esteban JM, Martín-Serra A, Varón-González C, et al. Morphological evolution of the carnivoran sacrum. J Anatomy. 2020;237:1087-1102.

- Moro D, Kerber L, Müller P, Pretto FA. Sacral co-ossification in dinosaurs: The oldest record of fused sacral vertebrae in dinosauria and the diversity of sacral co-ossification patterns in the group. J Anatomy. 2021;238:828-844.

- Ojumah N, Loukas M. The intriguing history of the term sacrum. The Spine Scholar. 2018;2:17-18.

- Stewart TA, Lemberg JB, Hillan EJ, Magallanes I, Daeschler EB, Shubin NH. The axial skeleton of tiktaalik roseae. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2024;121:1-9.

- Xia B, Zhang W, Zhao G, et al. On the genetic basis of tail-loss evolution in humans and apes. Nature. 2024;626:1042-1048.

Explore more on the sacrum in this issue of AAOS Now

- Disruptions of the SI joint and fractures of the sacrum associated with pelvic ring injuries

Regarding specific pathologies affecting the sacroiliac region, disruptions of the SI joints occur in many pelvic fracture patterns.

- Rare transverse sacral fractures pose high risk for neurological dysfunction

Injuries to the coccyx are often accompanied by transient or permanent genital-urinary problems. - Sacral bone tumors: balancing oncologic control with nerve preservation

Sacral bone tumors are rare and may be either benign or malignant. Of those that are malignant, metastatic disease (carcinoma or hematologic) far outweighs the number of primary bone malignancies.