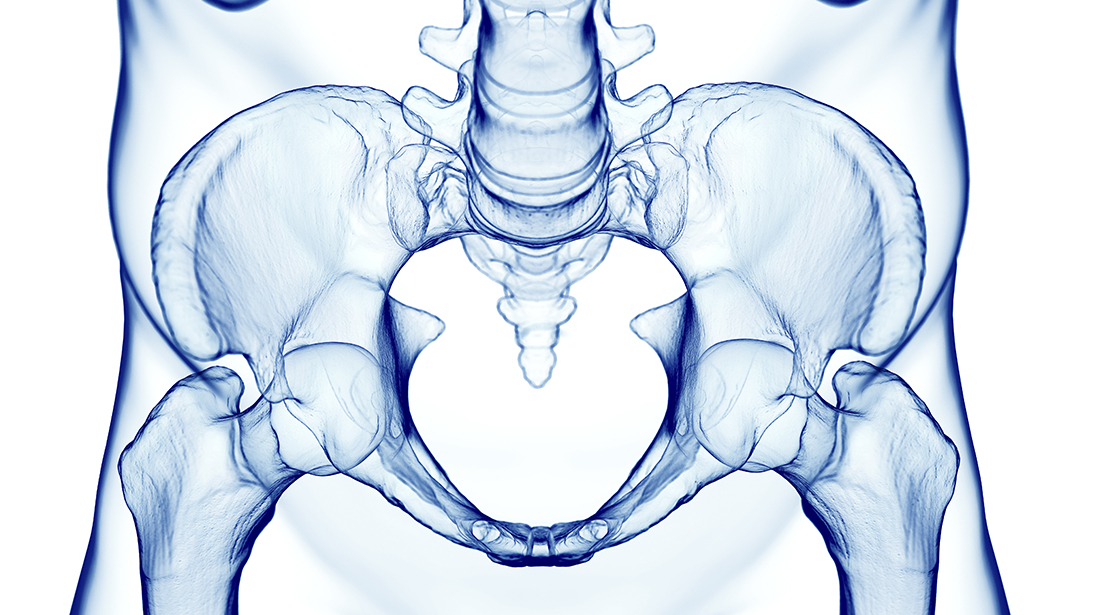

The sacrum has historically been referred to as the keystone of the pelvis given its central position as well as its articulation with the axial spinal column. The sacrum has adjacent sacroiliac (SI) joints, though cartilaginous, primarily function to provide shock absorption and stability to the pelvis during weight bearing. The anterior and posterior SI ligaments are incredibly robust and allow little motion during most activities.

Given the sacrum’s critical role in pelvic stability, injuries to the pelvic ring often involve this structure and the SI joints. Pelvic ring injuries result from direct or indirect forces to the bony pelvis, causing fractures and/or disruption to the osseous architecture or articular joints of the pelvic circle. The posterior elements of the pelvis, including the sacrum and the two SI joints, are key components of the posterior pelvic ring and are thus commonly involved in pelvic ring injuries. They are critically important to the pelvic stability, and comprehension of their anatomy and common injury patterns is important for any orthopaedic surgeon who may encounter this pathology.

Depending on force and mechanism, injury to the posterior pelvic ring may result in a fracture of the sacrum, a complete or incomplete disruption of the SI joint, or some combination of the two, such as a fracture-dislocation of the SI joint. The injury can be unilateral, bilateral, and may even be different from one side to another. Simple descriptive terms clearly describe traumatic injuries to the sacrum or SI joints. For example, sacral fractures can be “complete” or “incomplete” and can be described as “displaced” or “minimally displaced.” Further information with the location and orientation of the fracture line(s) can then be used to help improve description of the injury.

Accurate diagnosis requires radiographic and advanced imaging techniques

Radiographic evaluation of these injuries begins with plain radiographs, including anteroposterior, inlet, and outlet views of the pelvis. A lateral sacral view best depicts a coronal plane injury to the sacrum. However, a CT scan of the pelvis is key to understanding the exact location and severity of any injury to the posterior pelvic ring. Clinicians should recognize that plain radiographs and CT scans are static imaging modalities that may not accurately represent the degree of injury, especially in the SI joint involvement. Perform further manipulative or radiographic investigation, when indicated, to correctly identify posterior pelvic ring injuries.

Posterior pelvic ring injuries that involve the SI joints may disrupt the adjacent arterial or venous pelvic plexus, but the joints do not have the same intimate relationship with neurological structures that the sacrum does. The L5 nerve roots course over the anterior aspect of the upper sacral segment just medial to each sacral ala. The central sacral canal contains the sacral nerve roots that exit through the four numbered pairs of neural foramina (S1-S4). Sacral injuries, especially the more severe or displaced type, may injure or impinge on some of these neurological structures.

Pelvic ring injuries are frequently described using the Young and Burgess classification system based on the mechanism of injury. Disruption to the sacrum or SI joint(s) occurs in a spectrum based on mechanism of injury. Anterior-posterior compression (APC), lateral compression (LC), vertical shear (VS), and combined mechanism injuries can all lead to a range of instabilities based on patient and injury factors. While historical teaching focused primarily on restoring stability to the posterior pelvic ring, recent literature has shown the importance and contribution of the anterior pelvic ring to obtaining and maintaining reduction and stability of the posterior pelvic ring structures.

The “open book” APC pelvic ring injury most frequently results in a partial or complete injury to one or both SI joints but may also involve the sacrum. This volume-expanding pelvic injury enlarges the pelvic circle. If an incomplete injury exists, the strong posterior SI ligaments keep the most posterior osseous elements connected and can aid in reduction and fixation (APC 1 and APC 2). The APC 3 lesion represents a complete posterior SI disruption. In some injuries, a combined disruption through the SI joint occurs with an osseous fracture adjacent to the SI joint, or the posterior ring injury can occur completely through a vertically oriented and widened sacral fracture. The latter is less common but can result in significant morbidity.

Lateral compression injuries often involve the posterior pelvic ring, which reflects the direction of trauma. The LC 1 injury describes compression injuries to the ipsilateral sacrum and anterior ring. The overall stability or instability of the injuries is an active area of investigation and a perfect example of the relationship that the anterior and posterior pelvic ring have on stability of the other. The LC 2 injury describes a fracture dislocation of the posterior ilium through the SI joint (“crescent” fracture) along with an ipsilateral anterior ring injury. The LC 3 injury is the “windswept” injury, where one hemipelvis experiences a lateral compression injury, while the contralateral hemipelvis experiences an APC type injury with widening or external rotation through the posterior ring.

Finally, Vertical Shear (VS) injuries result in vertical displacement of a hemipelvis. This can occur through a vertical fracture of the sacrum or a SI joint. These injuries often occur after a fall from height or notable axial load through one or both lower extremities. In addition, some patients will present with a combined mechanism where one or more characteristic ring lesions are present. In these cases, descriptive terminology is again best used to note the location, type, and severity of injury.

Management strategies have progressed from traction to minimally invasive fixation

Treatment of posterior pelvic ring injuries has evolved over the last half century. Nonoperative management with prolonged skeletal traction was replaced by operative management with open fixation via extensive anterior and posterior approaches. These interventions were invasive and associated with complications related to soft tissue trauma and fixation implants, especially when present on the dorsal surface of the posterior pelvis. The development of percutaneous screw fixation of the sacrum and SI joints revolutionized treatment of the posterior pelvic ring. Contemporary pelvic trauma surgery with percutaneous implants relies on understanding pelvic fixation pathways and mastering techniques for safe implant placement under standard intraoperative fluoroscopy.

Posterior pelvic ring trauma spans a spectrum from low energy fragility fractures in the elderly to high energy trauma that can be imminently life threatening. Reduction and stabilization of the posterior elements is critical to everything from initial hemodynamic resuscitation in the polytraumatized patient to pain control and eventual patient mobilization. A complete understanding of pre- and intraoperative radiographic imaging is essential to safe and successful diagnosis and management. Technology will continue to improve implants and techniques we use for fixation of the SI joints and sacrum, but understanding of the anatomy, injury patterns, and basic fracture fixation principles will not change.

John A. Scolaro, MD, MA, FAAOS, is an orthopaedic surgeon at the University of California, Irvine – Department of Orthopaedic Surgery.

References

1. Bellabarba C, Stewart JD, Ricci WM, DiPasquale TG, Bolhofner BR. Midline Sagittal Sacral fractures in anterior—posterior compression pelvic ring injuries. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma. 2003;17:32-37.

2. Blum L, Hake ME, Charles R, Conlan T, Rojas D, Martin MT, Mauffrey C. Vertical shear pelvic injury: evaluation, management, and fixation strategies. International Orthopaedics. 2018;42:2663-2674.

3. Ellis JD, Shah NS, Archdeacon MT, Sagi HC. Anterior pelvic ring fracture pattern predicts subsequent displacement in lateral compression sacral fractures. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma. 2022;36:550-556.

4. Kumaran P, Wier J, Patterson JT, et al. Percutaneous anterior pelvic ring fixation in addition to percutaneous posterior pelvic ring fixation decreases postoperative pain and narcotic usage in hospital for lateral compression types 1 and lateral compression type 2 injuries. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma. 2025;39:61 5–620.

5. Kuršumović K, Hadeed M, Bassett J, Parry JA, Bates P, Acharya MR. Lateral compression type 1 (lc1) pelvic ring injuries: a spectrum of fracture yypes and treatment algorithms. European Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery & Traumatology. 2021;31:841-854.

6. Tempelaere C, Vincent C, Court C. Percutaneous posterior fixation for unstable pelvic ring fractures. Orthopaedics & Traumatology, Surgery & Research. 2017;103:1169-1171.

7. Vaidya R, Oliphant BW, Hudson I, Herrema M, Knesek D, Tonnos F. Sequential reduction and fixation for windswept pelvic ring injuries (LC3) corrects the deformity until healed. International Orthopaedics. 2013;37:1555-1560.

8. Young JWR, Burgess AR. Radiologic Management of Pelvic Ring Fractures: Systematic Radiographic Diagnosis. Baltimore: Urban & Schwarzenberg; 1987.