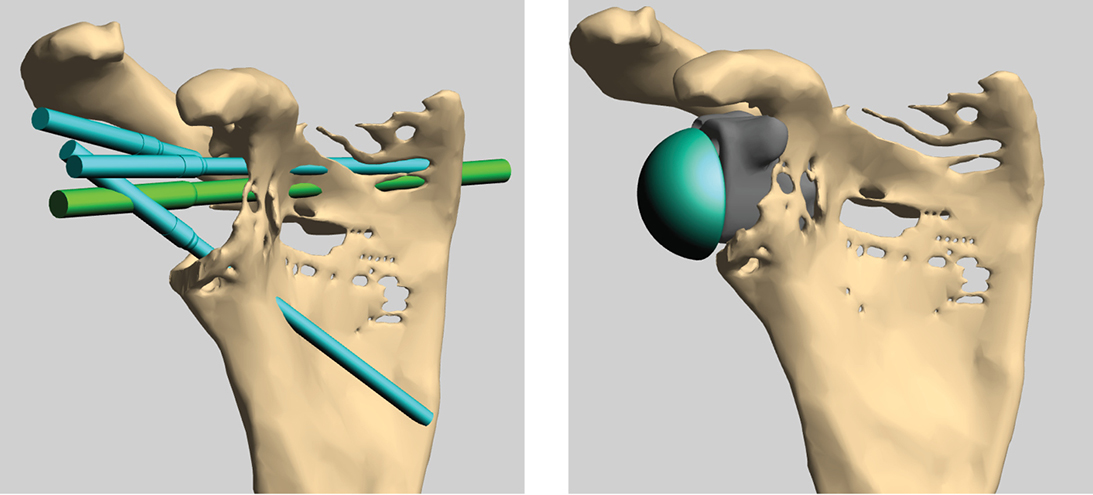

Figure 2: Digital model of custom glenoid baseplate with standard glenosphere attached.

Varying degrees of glenoid bone deficiency to be addressed at the time of primary total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) can occur as a consequence of natural disease processes. Additionally, some of the most challenging glenoid deficiencies can occur in the setting of revision arthroplasty.

As the number of patients treated with shoulder arthroplasty continues to rise, it is an expected consequence that the prevalence of failed arthroplasty in need of revision also rises. Revision shoulder arthroplasty is predominantly in the form of a reverse TSA (rTSA) due to the common presence of rotator cuff deficiency and the ability to address stability and bone stock deficiency more effectively than with prior techniques relying on anatomic designs. Nonetheless, glenoid bone deficiency is a common source of complexity necessitating any number of advanced techniques to sufficiently restore or lateralize the joint line, achieve stable implant fixation, and avoid humeral impingement.

Several techniques for addressing glenoid bone loss in the primary and revision settings are commonly employed in current practice. Eccentric glenoid reaming is a traditional and relatively straightforward method of managing eccentric bone loss and restoring appropriate version and inclination when adequate residual bone stock can be maintained. However, the technique can contribute to joint line medialization and loss of bone available for implant fixation at the time of the index procedure or any subsequent procedures. It can also contribute to scapular impingement and notching. Shifting the position of the glenoid baseplate to allow for fixation into the best available bone is also used successfully in cases of mild to moderate glenoid deficiency. In cases of moderate bone loss not suitable for eccentric reaming, bone grafting and prefabricated augmented baseplates can be used to increase bone support of the implant while achieving adequate alignment correction. In order to ensure implant stability, most surgeons aim to have at least 50% to 80% of the baseplate supported by the intact glenoid surface.

For cases of severe multiplanar glenoid deformity and deficiency, techniques for restoration with either bone graft or augmented implants have been developed. The Bony Increased Offset Reversed Shoulder Arthroplasty (BIO-RSA) technique described by Boileau involves use of a large bone graft fully interposed between the native glenoid and the baseplate to lateralize the center of rotation and allow for angular correction. A potential advantage of this technique is its ability to restore scapular bone stock through graft incorporation to facilitate future revision arthroplasty. This bone restoration can be an important consideration, particularly in younger and more active patients who may be at increased risk of future implant failure. The technique can often be performed with humeral head autograft in the setting of primary arthroplasty, and excellent functional outcomes with low revision rates have been reported. However, autograft bone is typically not available when this technique is used in the revision setting; allograft, commonly sourced as fresh frozen femoral head allograft, may have poorer rates of bone incorporation. Immediate surgical fixation of the graft also relies on use of screws placed through standard holes of an off-the-shelf baseplate. Adequate fixation can be expected when superior, inferior, and either anterior or posterior screws with good purchase are available. However, in some cases, a staged procedure to allow for bone incorporation may be prudent when early stability is questionable.

An alternative method of restoring the glenoid joint line and alignment is through the use of a custom metallic glenoid component. With this technique, a preoperative CT scan is used to create a 3D model of the glenoid bone defect. A rendering of a potential custom glenoid component is then created to fill the deficiency and provide the desired amount of joint-line lateralization and angular realignment. Additionally, screw trajectories can be placed anywhere within the implant to best utilize the remaining host bone for stable fixation. Standard glenospheres are typically affixed to this custom baseplate to complete the glenoid reconstruction. There are several potential advantages to this technique beyond the ability to restore glenoid anatomy. Although bone stock is not augmented as with BIO-RSA, minimal bone removal is required and hence native anatomy is left largely unchanged. The custom implant is equally able to address uncontained cavitary defects as well as contained ones. The ability to customize the position of screw holes facilitates intraoperative efforts to achieve adequate fixation and removes the constraints of any fixed or variable locking screw holes on a standard baseplate, which can only be modified within narrow limits. No additional operating time is required to shape the implant, as with the use of bone graft. The region of bone contact achieves long-term fixation with the same ingrowth surfaces utilized in off-the-shelf baseplates. The use of a large metallic implant rather than bone graft also removes the long-term concern for graft resorption and subsequent implant loosening.

Although cost and lead time to design and manufacture custom metallic glenoid components are potential drawbacks to this technique, both these factors have decreased over time and are likely to see further improvements as the technology matures. As stated above, bone augmentation to facilitate future revisions is not achieved, but the bone stock would be expected to remain in largely its current state to allow for the same technical options available at the index procedure. Precise alignment of the implant to match preoperative templating is also critical in cases of severe bone loss in order to achieve the maximal screw fixation predicted. Use of patient-specific guides and/or navigation would likely facilitate this recreation of planned alignment. Additionally, implant tabs that overlap prominent edges or other significant glenoid landmarks and ensure precise fit of the bone-implant contact make the correct orientation more obvious at the time of surgery.

Achieving stable fixation of a well-positioned glenoid component is commonly the most challenging aspect of rTSA. In the face of major bone loss, these challenges can be substantial, and the presence of multiple potential solutions remains beneficial. Custom 3D printing of a glenoid baseplate can move most of the planning to the preoperative period and allow for maximal restoration of desired joint-line position and alignment without some of the uncertainties inherent in the use of bone graft. Evolution of current techniques and longer-term follow-up will assist the revision arthroplasty surgeon in choosing the optimal technique in these complex surgical cases.

Robert M. Orfaly, MD, MBA, FAAOS, is a professor in the Department of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation at Oregon Health and Science University. He is also the editor-in-chief of AAOS Now and chair of the AAOS Now Editorial Board.